Is Italian truly the most beautiful language in the world, as a new trend in Italian public discourse seems to suggest? The titles of some recent books speak for themselves: from Geppi Patota’s La grande bellezza dell’italiano: Dante Petrarca Boccaccio (2015), Annalisa Andreoni’s Ama l’italiano: Segreti e meraviglie della lingua più bella (2017) and Claudio Marazzini’s L’italiano è meraviglioso: Come e perché dobbiamo salvare la nostra lingua (2018) up to Stefano Jossa’s La più bella del mondo: Perché amare la lingua italiana (2018), it is all a celebration of the beauty of the Italian language. So much so that an influential academic and journalist, Matteo Motolese, Professor of History of the Italian Language at the University of Rome “La Sapienza” and columnist for the Italian daily newspaper il sole 24 ore, has aptly and humorously spoken of the birth of a new literary genre, the eulogy of the Italian language. The very media friendly Prof Giuseppe Antonelli, another leading historian of the Italian language, has more recently reached the point of suggesting a museum of the Italian language. There is little surprise, though, since in the last decade “beauty” has certainly entered the Italian public discourse as a new unifying keyword, from Roberto Benigni’s TV show dedicated to the Italian Constitution, entitled La più bella del mondo (2012), to Paolo Sorrentino’s Oscar-winning film La grande bellezza (2013) – clearly echoed in the titles of Jossa and Patota’s books.

Is Italian truly the most beautiful language in the world, as a new trend in Italian public discourse seems to suggest? The titles of some recent books speak for themselves: from Geppi Patota’s La grande bellezza dell’italiano: Dante Petrarca Boccaccio (2015), Annalisa Andreoni’s Ama l’italiano: Segreti e meraviglie della lingua più bella (2017) and Claudio Marazzini’s L’italiano è meraviglioso: Come e perché dobbiamo salvare la nostra lingua (2018) up to Stefano Jossa’s La più bella del mondo: Perché amare la lingua italiana (2018), it is all a celebration of the beauty of the Italian language. So much so that an influential academic and journalist, Matteo Motolese, Professor of History of the Italian Language at the University of Rome “La Sapienza” and columnist for the Italian daily newspaper il sole 24 ore, has aptly and humorously spoken of the birth of a new literary genre, the eulogy of the Italian language. The very media friendly Prof Giuseppe Antonelli, another leading historian of the Italian language, has more recently reached the point of suggesting a museum of the Italian language. There is little surprise, though, since in the last decade “beauty” has certainly entered the Italian public discourse as a new unifying keyword, from Roberto Benigni’s TV show dedicated to the Italian Constitution, entitled La più bella del mondo (2012), to Paolo Sorrentino’s Oscar-winning film La grande bellezza (2013) – clearly echoed in the titles of Jossa and Patota’s books.

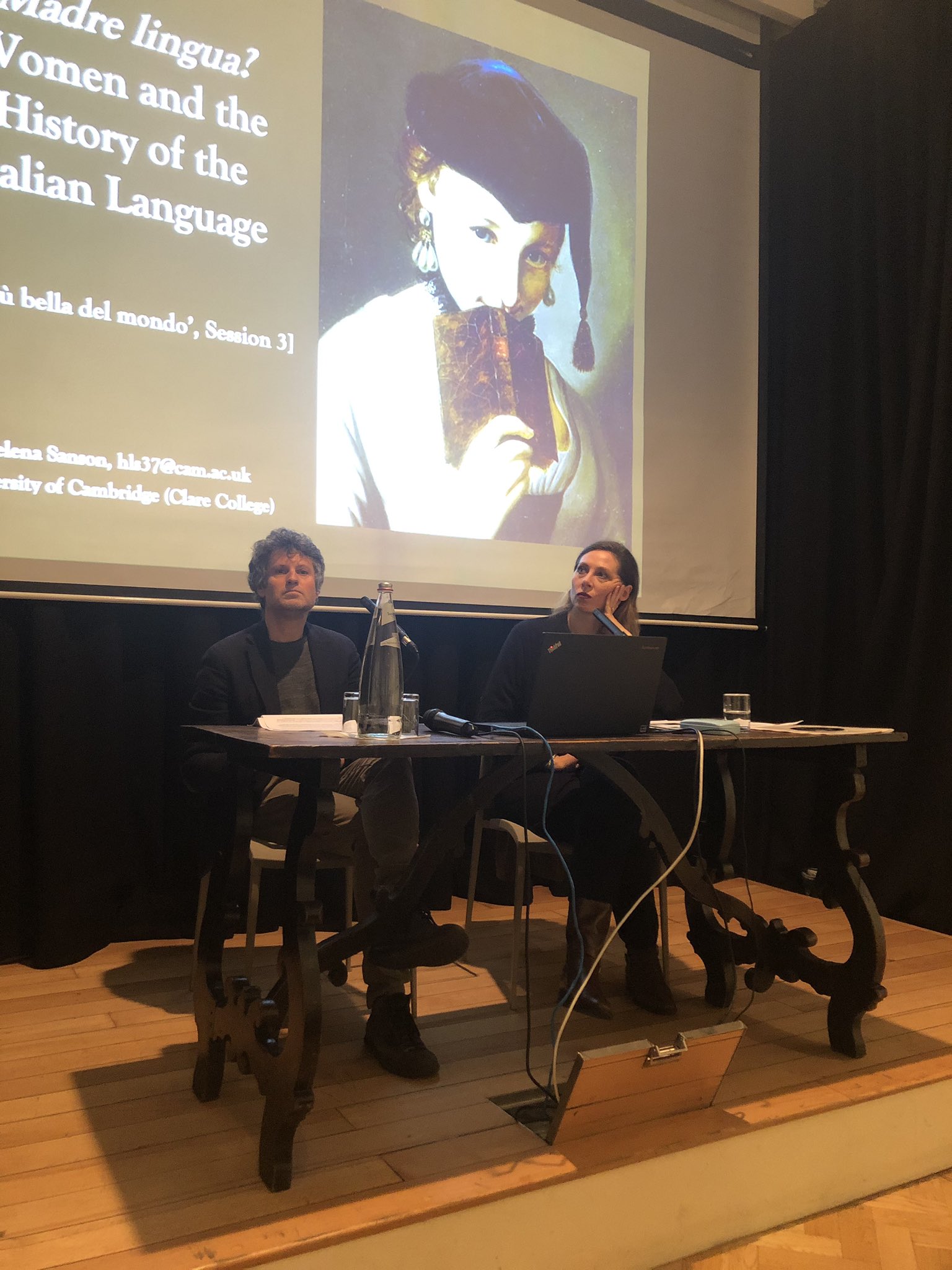

A series of ten meetings at the Italian Cultural Institute in London, led by academic and critic Stefano Jossa (Royal Holloway, University of London) from January to June 2019, has explored the issue in depth, with the aim of assessing the supposed beauty of the Italian language and demonstrating the extent to which the work of Italianists and linguists in the UK is of relevance to what is going on in Italy at present. Alternating popular voices from the Italian linguistic field (such as Matteo Motolese, Massimo Arcangeli, author of Sciacquati la bocca: Parole, gesti e segni dalla pancia degli italiani, and Geppi Patota, author of what looks now as the second instalment in a series, La grande bellezza dell’italiano: Il Rinascimento) and British and Italian linguists and non-linguists working in the field of Italian Studies in the UK (including Robert Gordon, Helena Sanson, Francesco Goglia, Caterina Sinibaldi, Federico Faloppa and Alessandro Carlucci), the series has explored issues of linguistic interference, anglicisation of Italian, multilingualism, the language of women and immigrants, the use of insults as well as racism and offense in language.

Thomas Mann, is well known, had little doubt that “angels in the sky speak Italian” (Confessions of Felix Krull): a phrase often quoted by the ones who support the view that Italian is actually “the most beautiful language in the world”. However, the words in Mann’s novel are uttered by Felix Krull, who is famously an impostor and therefore unreliable. More seriously, the most beautiful language in the world simply does not exist, because there is no scientific way to determine the beauty of a language. And yet German philologist Harro Stammerjohann has demonstrated that Italian has historically been associated with such words as armonioso, delicato, dolce, elegante, fluido, gentile, gradevole, grazioso, liscio, melodico, piacevole, and seducente (La lingua degli angeli: Italianismo, italianismi e giudizi sulla lingua italiana): from Milton, who equated Italian to “the language of love”, and Charles V, who legendarily said that “he spoke Spanish to God, Italian to women, French to men, and German to my horse”, up to John Dryden, who famously claimed that Italian “is the softest, the sweetest, the most harmonious, not only of any modern tongue, but even beyond any of the learned” (Albion and Albanius) and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who maintained that “s’il y a en Europe une langue propre à la musique, c’est certainement l’Italienne; car cette langue est douce, sonore, harmonieuse, et accentuée plus qu’aucune autre, et ces quatre qualités sont précisément les plus convenables au chant” (Lettre sur la musique françoise), Italian seems to have been unequivocally discussed from an aesthetical point of view. When it came to the definition of the creative power of human mind, the German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz, who wrote in French, could only resort to Italian to express the concept of “l’invenzione la piu’ bella” (the most beautiful invention), which could not be said, in his views, but in Italian (Essais sur l’entendement humain).

Who is right and who is wrong is, once again, a matter of subjective judgment. What the series has demonstrated is that Italian is part a global web of languages that still needs variety to achieve beauty and creativity.