Dr Elena Minelli (University of Bath)

My teaching/learning context

The students enrolled in a BA (Hons) in Modern Languages at the University of Bath (3 years + Year Abroad) start studying Italian ab initio. After an intense language course in the first year, they progress to reach level C1 (CEFR) by the end of the final year. The time spent in Italy during their year abroad is crucial for their language improvement and their understanding of Italian culture.

Being a lecturer as well as the Year Abroad Officer for Italy, I usually visit students on placement during our November Reading week. Some of them work as Language Assistants in schools in the north of Italy. It was during one of my visits that a student told me she had witnessed episodes of racial intolerance and racism among the school children and, most sadly and worryingly, among some teachers. Coming from a British educational background, the student was shocked: she felt uncomfortable and immediately expressed her disappointment to the children. This year, another student of Afro-Caribbean origin, who is completing her year abroad in Sardinia, reported feeling uncomfortable on a few occasions, when Italian people looked at her suspiciously because of her ethnic origin. Their attitude only changed when she revealed her nationality: ‘Ah! Ma sei inglese allora!’.

Episodes like these made me realise that, as an educator, I have the moral responsibility to prepare our students for what they may face when they arrive in Italy. Students should be aware that they may witness racist behaviour towards other people or themselves, and they should have the chance to reflect on their own experience and share it when they come back in their final year. I realised that the involvement of students in re-shaping the Italian curriculum according to principles of Equality, Diversity and Inclusion could be a very interesting topic for a Teaching/Learning Development Project.

What has inspired me?

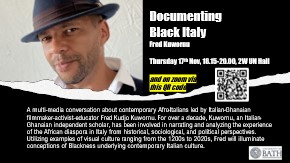

With these educational prerogatives in mind, I enrolled in the very first edition of the 5-day intensive online Summer School ‘Teaching Black Italy’, funded by the film/doc producer, activist and educator Fred Kudjo Kuwornu in June 2021. It was a unique experience I had the privilege to share with teachers and lecturers in Italian Studies from all over the world. We met several Afroitalians born in Italy or emigrated to Italy in the early ’90s (the so called ‘Balotelli generation’), who narrated their moving and remarkable stories; we found out about their challenges, their battles, but also their talents and great achievements. We discovered how they managed to become ‘visible’ in a country that was not ready to accept them, and to become successful in various artistic fields – including cinema, music, writing, painting – despite living in Italy. For me, it was like opening a Pandora’s box!

One thing the Summer School did not tell us, however, was how we could use that vast amount of information and material, how we could embed it within our courses and curricula: At what level? In what shape and form?

I strongly believe that motivation and inspiration often come from personal experience. For me, it was the need to put a missing piece to the jigsaw puzzle of my knowledge to gain a better understanding of immigration in Italy. I left Italy in 1994, when the stories of the Afroitalians at the Summer School begin. Having left Italy, I never knew what happened to the children of the immigrants who came to the north of Italy in the early ’90s to work in industrial areas around Bergamo and Brescia. At the Summer School, I was impressed particularly by three people: the rapper Tommy Kuti, who emigrated to Italy as a child with his Nigerian parents and landed in a small village in Vallecamonica (Esine, Lombardy), where I used to spend time at my grandparents’ house; the writer and documentary maker Marilena Delli Umuhoza, born and brought up in a small town next to mine (Alzano, Lombardy) with an Italian father (‘un vero bergamasco’) and mother from Rwanda; and Angela Haisha Adamou, a young professional woman of Ghanaian origin, who was born and lived in Correggio (Emilia Romagna).

It was a good starting point for me. In the following sections, I am going to take you through the journey I undertook with my students to raise awareness on what it means to be black in Italy today.

You have to start somewhere!

First, I followed Tommy Kuti on his Facebook page and tried to contact him via Messenger. As he did not respond, I decided to leave it for the time being. Instead, I used his video ‘Sono afroitaliano’ to introduce the topics ‘Gli afroitaliani’ to my second and final year students. I strongly recommend this video, which is powerful in its simplicity: ‘Sono troppo africano per essere solo italiano e troppo italiano per essere solo africano. Sono afroitaliano’. Every time I play it in class, my students are drawn to it and, in the end, they are ready to learn more about the topic.

You can find out more about Tommy Kuti and his campaign for inclusion and diversity here.

Project 1: Angela Haisha Adamou in conversation with my final year students

I then contacted Angela Haisha Adamou, a young entrepreneur who set up her own online business, NaturAngy Academy, offering advice and support with treating the hair of Afro-Caribbean girls/women. I was pleased to see that Angela replied immediately and she was happy to collaborate. Bingo! I invited her to join one of our final year language classes in a video call. The aim of the meeting was to get her to share her experience as a young successful Afroitalian woman, who was born and brought up in a provincial town in central Italy.

The outcome of the meeting exceeded my expectations. The 50 minutes conversation was carried out entirely in Italian, and Angela’s pace and vocabulary were perfect for the level of my students. Angela touched upon many issues, starting from how she set up her hairstyling business while she was still at the liceo scientifico. She explained that, in Italy, African girls from an early age have difficulties in ‘fitting in’, also because their hair is different and Italian hairdressers cannot treat it properly. Hence, young girls may develop low self-esteem. Angela confessed that her business originated from her own need to remove an obstacle in her childhood and help other young girls do the same. She also talked about the challenges she faces on a daily basis as an African young woman living in Italy. An example was the question ‘Ma come fai tu ad avere una macchina nuova?’ (meaning: ‘is this new car really yours or have you stolen it?!’) she was asked once by an Italian young man. A student was intrigued and wanted to know how she responded to such a question, and she explained that she simply replied ‘e tu?’, cleverly putting herself on the same level as her interlocutor.

Angela also made us aware that the black female body is sexualised in Italy, which means that as a little girl she had to learn that wearing the same skimpy skirts her female friends were wearing could lead to a misinterpretation of her behaviour. On a positive note, Angela felt privileged because she was able to realise her dreams. Talking to Angela about her successful business allowed me to address another crucial topic with our final year students: employability from an EDI perspective. Angela gave our students practical tips on how to set up a successful business and talked about her passion, her resilience, and her belief in what she was doing – a very good lesson for our students to take home! In the end, we were all happy to hear that Angela was studying to obtain a degree in Law: one day she would make a real difference by offering substantial help to ethnic minorities and to unprivileged people in Italy.

During our meeting, students asked Angela a few questions. However, it was only in our follow-up session that they opened, talking about their opinions and concerns and sharing their personal experience. A student who had worked as a Language Assistant in Spain in her year abroad remembered a colleague with Afro-Caribbean origin constantly complaining because she could not find a hairdresser who could treat her hair properly. She was forced to keep it short!

I was very pleased about the outcome of this mini-project, which had involved three stages: 1. preparing the students with key Italian words and ideas for possible questions to ask Angela; 2. organising and facilitating the video call in collaboration with two invaluable colleagues of our Italian team; 3. running a follow-up/debriefing session with the students and collecting informal feedback. Students were very engaged throughout the activities: Angela had helped them reflect on their experience in Italy and understand it better.

You can find out more about Angela Haisha Adamou’s experience and her successful business in this video.

Projects 2 and 3: Reading extracts from short novels and watching parts of the Netflix series Zero with second-year students

I then contacted the writer, film producer, photographer and activist Marilena Delli Umuhoza and invited her to attend a panel in our Seminar on Italian Postcolonial Female Writers. Marilena accepted the invitation and was very pleased to hear that we were ‘neighbours’ in Italy, which allowed me to understand well the reality she had depicted in her autobiographical novel Negretta: Baci razzisti (2020). I had read the book and I was very impressed by it. I would certainly recommend it to anyone who wanted to introduce texts of Afroitalian writers to intermediate-advanced students of Italian. It is a moving and powerful report of Marilena’s childhood in the early ’90s, when she was brought up in a small right-wing provincial town near Bergamo and lived with her mum and dad on the company site where her father worked for very low wages. Although her father was proud of being ‘un vero bergamasco’, he had been rejected by his own family and friends because he had married a black woman. In turn, her mother had escaped the Rwandan genocide to find herself transplanted into an alien and hostile reality. Marilena’s strong passion for studying and her dedication allowed her to become ‘visible’ at school by shining in all her subjects and earning the praise of her teachers. We read a few extracts from her book in class and translated some expressions written in ‘dialetto Bergamasco’. Reading the dialectal expressions Marilena’s father occasionally used was very important for me, as it made me reflect on the expressivity of a local reality I knew very well. Reciting and translating short dialectal expressions with students was fun and it gave me the opportunity to introduce the concept of Italian dialects. I talked about the strong emotional power they can convey and, in doing so, I was touching upon another relevant aspect of EDI: language diversity and personal identity vis-à-vis social identity.

You can read more about Marilena Delli Umuhoza and her anti-racial campaigns here.

Last but not least, I wanted to use some video material with my second-year students. The Netflix series Zero (2021), based on Antonio Dikele Distefano’s book Fuori Piove, Dentro Pure, Passo a Prenderti? (2015), appeared to be a very good option. Dikele Distefano is a writer and rapper, who was born from Angolan parents in Busto Arsizio in the early ’90s but lived most of his life in Ravenna, where this book is set. His book is a love story between two young people: Antonio, a black boy; and Benedetta, a girl whose family cannot accept her boyfriend on the grounds of the colour of his skin. Fred Kudjo Kuwornu had recommended this book and the Netflix series during the Summer School. He had told us that Zero has a special place in the filmic production about Afroitalians, because it is the very first TV series (and movie) where all actors are black. In Distefano’s novel, each chapter is introduced by the lyrics of the song playing in the background when the author was writing that chapter. I thought that mixing music, lyrics, texts, and videos could lead to an interesting multi-media and intertextual exploration of the theme. We read a few extracts from the book together, listened to the songs, watched a few scenes from Zero and discussed them in class. As a follow-up activity, the students had to watch at least one episode of Zero and be ready to discuss it. The outcome was very positive, and the students were fully engaged throughout the activities, particularly those based on the videos. As a reading text for the May Exam, I chose an interview with Dikele Distefano, where the author explains how writing helped him overcome big challenges in his life and facilitated his way to integration. I was pleased to see that the students were very well prepared for this topic and performed well in the exam😊.

If you want to know more about Antonio Dikele Distefano, I recommend this interview: among other things, he touches upon the right of citizenship for immigrants who are born and/or brought up in Italy (ius solis and ius culturae vs ius sanguinis). Distefano believes that the real problem is not so much receiving the occasional insults, which could be due to ignorance or lack of good manners, but the lack of recognition of the right of citizenship, which could allow Afroitalians and other ethnic minorities to be fully integrated and ‘visible’ in the country where they live.

I have mentioned here only a few of the activities and projects I have carried out over the past four years, and there is still a lot to do! I hope I have given you some ideas and inspiration for your own teaching and/or curriculum development. If you are interested in sharing ideas and/or collaborating to create teaching/learning material for students of Italian, I would be very happy to hear from you! This is my email address: e.a.minelli@bath.ac.uk.